Portraiture and Academic Work

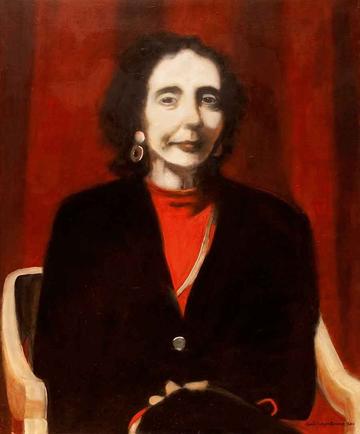

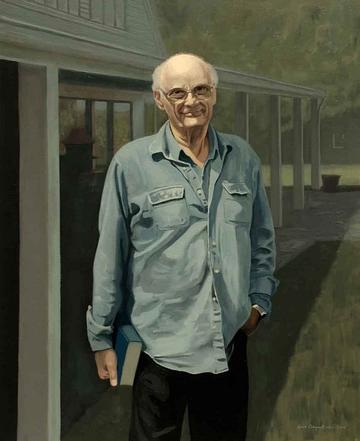

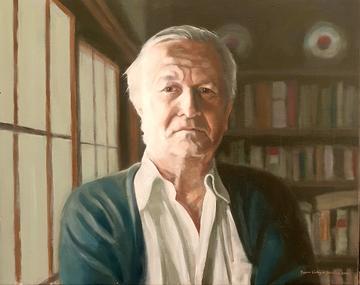

On 1 March, the RAI is hosting a viewing and discussion with artist and academic Gavin Cologne-Brookes, Emeritus Professor at Bath Spa University. Gavin has loaned the RAI four of his portraits, depicting the writers Joyce Carol Oates, William Styron, and Arthur Miller, and the musician Bruce Springsteen. They are currently on display in the Vere Harmsworth Library. In this article, he shares the fascinating way in which these portraits were conceived and created.

When I write about a writer, I contemplate a personality: not just their subject matter but their approach. We’re always reading someone, and as someone. The same applies to all writing and all encounters. We project our own preoccupations and personality onto the world. In David Bromwich’s words, we’re all “Novelists of Everyday Life.” To paint a writer’s portrait is another way of contemplating that person. It involves attention to features and expression, but from one’s own perspective. As with word choice, every paint fleck is personal.

I began oil painting long before academic research. We draw before we write. Neurologist Semir Zeki, in Inner Vision: An Exploration of Art and the Brain, notes that a painting “is often able to communicate visually what words are unable to do.” The reason may be found “in the greater perfection of the visual system, which has evolved over many more years than the linguistic system.” The eye sees in a second what words might take paragraphs to explain. But hard as it may be to describe visual art, the visual can enhance our writing.

The portrait of Joyce Carol Oates is how I saw her when we talked in Chicago in 2010. It’s a portrait of self-possession but her sensitivity means she’s fully aware of the nature of unease. Dark Eyes on America (2005) is about any well-adjusted individual’s trajectory toward maturity: from I to we, self to others, looking inward to looking outward. This author is far more interested in you, the viewer, than in herself.

The portrait of William Styron resulted in a critical memoir. My earlier book, The Novels of William Styron (1995), began as my PhD. As a young man I wanted to meet and learn from this novelist. Our 1988 conversations in Roxbury, Connecticut, form an appendix. After Dark Eyes on America, I sought a more creative, visual form of criticism. Using a photo I’d taken when we first met, I painted the portrait while listening to a recording of Sophie’s Choice. I’d earlier painted his Roxbury neighbour, Arthur Miller.

During the process I planned Rereading William Styron (2014). I’d explore the meaning of rereading and combine relative critical objectivity with a personal story. I’d describe befriending the author. I’d situate reading the fiction in the context of actual life. I’d include a memoir of visiting the New York and Tidewater Virginia settings of the novels and parenthesize the Sophie’s Choice chapter within trips to Kraków and Auschwitz. (A later essay, “Rome to Ravello with Set This House on Fire,” describes a journey through the Italy of that novel.) The portrait would be the book’s cover: not Styron himself, but my rereading of him. For what struck me was that in my twenties I’d viewed him as a Famous Author, whereas the portrait shows a more complex, vulnerable man.

The Bruce Springsteen portrait reversed the portrait-to-book process. Springsteen’s public profile is greater, his audience demographics more diverse. Again I took an art-in-life approach, from cultural commentary to memoir. I envisaged different readers gravitating to different chapters. Meanwhile, I contemplated a cover portrait. Using video footage, I created an image that doesn’t exist as a photo. It’s the only one of the portraits where the subject is looking downward rather than at you. Even as he engages with his audience, Springsteen also has a deeply introspective side.

My kind of oil painting is not unlike creating a manuscript. I start with an overall concept. The oil takes two days to dry so each session requires time-limited focus. Sometimes I attend to the whole, other times to detail. Returning to it with a more objective eye, I edit and redraft, much as with sentences, paragraphs, chapters. Tolstoy famously quotes the artist, Karl Bryullov, saying that “art begins where the tiny bits begin.” If I get the small things right I produce a convincing whole. The same goes for a book. And while a book takes time to read and a painting a moment to view, the main thing we retain is that overall impression.