Reflections from the Winant Chair

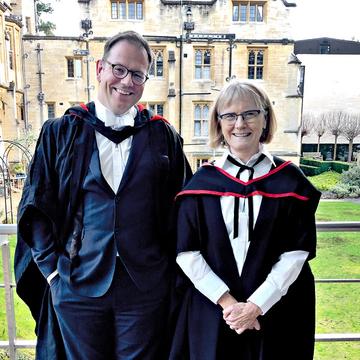

Each year, the John G. Winant Visiting Professorship of American Government brings to Oxford an eminent scholar of American politics and government. As we prepare to welcome this year's holder, Robert Lieberman of Johns Hopkins University, we take the opportunity to thank the previous Winant Professor, Margaret Weir (Brown University), for her great contribution to the intellectual life of the RAI. Her account of her tenure of the chair appears below, as published in the Institute's Annual Report for 2019-20.

Professor Weir writes: It was a great honour to serve as the John G. Winant Chair of American Government. My time in Oxford was sweet but, due to the pandemic, regrettably short. I arrived in January when the dark descends before 4.30 in the afternoon and left at the end of Hilary term just as the beauty that is Oxford in springtime began to reveal itself. Although I was only in residence for one term, it was an absolute delight to participate in the intellectual life of the Rothermere American Institute and Oxford more broadly.

My Winant inaugural lecture, entitled 'The Problem of the Public in Postwar America' examined the interplay between racial inclusion and public life in postwar America. Drawing from my research on metropolitan America, the lecture argued that federal and state policies segmented public life in two ways that enforced racial inequalities. Horizontal segmentation allowed local political boundaries to divide populations by race and income, creating severe imbalances between local public resources and fundamental services, including education. Vertical segmentation, which since 1980s has reduced federal place-based assistance, greatly exacerbated local resource inequalities. Rather than cushion the local imbalance between resources and needs, the federal government expected localities to solve their own problems through fiscal responsibility. The consequences of segmenting the public sector horizontally and vertically have reverberated throughout metropolitan America. They have stymied the development of the metropolitan public infrastructure and left some cities without basic services. At the same time, they have distorted ideals of democracy held by higher-income Americans, who now view local democracy as the right to be free from the burden of redistribution. These themes appear in my co-edited book Who Gets What: The New Politics of Insecurity, forthcoming from Cambridge University Press.

My colleague at Balliol, Sudir Hazareesingh, invited me to give a lecture on race in American politics to his undergraduate course 'Introduction to Politics.' In this lecture I examined the way racial exclusion and racist stereotypes have shaped America’s welfare state and party politics. Building on my research on New Deal and Great Society social policy, I discussed how American social benefits are split into a top tier of federal benefits for the elderly with long work histories and a bottom-tier of spotty and limited benefits provided by the states. The lecture showed how American party politics have become split along racial lines, with the great majority of Black and Latinx people supporting the Democratic party and whites favoring Republicans. I concluded by considering how demographic shifts, which are reducing the percentage of white Americans, will influence American politics. Emphasizing that "demography is not destiny," I highlighted the way that American electoral institutions, including gerrymandering and the electoral college, may blunt the impact of demographic change.

I found life at Oxford, both formal and informal, full of opportunities to learn from a wide variety of lectures and to interact with a remarkable range of scholars and public figures. At the RAI, I participated in the annual 'Congress to Campus' program, moderating a panel with two former members of Congress, Elizbeth Esty and Jeff Miller. The RAI’s Politics and History seminars offered a stimulating setting to reconsider American politics from new perspectives. And talking with graduate students during the weekly coffee hours gave me insights into American history and politics far from my areas of expertise. During meals at Balliol, Nuffield, St. Anne’s, Lincoln, and St. Peter’s, I enjoyed meeting scholars from diverse disciplinary backgrounds as well as public officials and journalists.

As life went virtual after March, I was pleased to participate in RAI Director Adam Smith’s new podcast series The Last Best Hope? Understanding America from the Outside In. We had a lively discussion centred on the question of whether a country, like the United States, that has had a successful revolution is doomed endlessly to re-enact it. We began with the alarming spectacle of armed white men entering American state legislatures, demanding that the stay-at-home orders related to the pandemic be lifted. Charging that the state government had impinged on their freedoms, these protesters waved confederate flags as well as a flag from the time of the American Revolution known as the 'Gadsden flag.' Bright yellow and emblazoned with a coiled rattlesnake snake ready to strike, the flag reads "Don’t Tread on Me." We talked about how anti-government activists have used language and symbols from the American Revolution relating to rebellion and freedom to support their aims, ranging from opposition to taxes to refusal to wear masks during the pandemic. We ended on a different note, considering how symbols of equality stemming from the American revolution have been used by African-Americans in their centuries-long struggle for freedom.

I had a chance to reflect on the differences between the response to the COVID pandemic in the United Kingdom and America in a short article entitled 'The Pandemic and the Production of Solidarity', published in Items, the Social Science Research Council’s online newsletter. I argued that national emergencies, such as the pandemic, inspire solidarity but that enduring solidarity requires public action. In comparing the United Kingdom and the United States I examined differences in existing institutions, strategic decisions, and public leadership regarding racial and ethnic differences in producing solidarity. Neither country responded effectively when the virus first hit. Despite some skepticism from British observers, I argued that Britain’s existing health care institutions and its public decisions about how to provide economic support during the pandemic set the stage for building more solidarity than in the United States. America’s inequitable health care system and its scattershot approach to economic security compounded inequality, generating frustration and mistrust. In Britain, both major political parties have acknowledged that the racial and ethnic disparities evident in the pandemic are a matter of public responsibility. By contrast, in America, key public leaders have dismissed the toll the virus has exacted on communities of color. Changing course will not be easy for the United States, but it is essential if the country hopes to emerge from the pandemic stronger and united, not weaker and divided.

It was my privilege to serve as the Winant Professor and to be part of the vibrant intellectual life at the University of Oxford. I look forward to the day when the pandemic has ebbed and I can return for a visit to see students reading on the college lawns and the spring in full bloom.