Women’s Worlds: New Histories of the United States and the World (Part 1)

As part of the American History Research Seminar’s “Women’s Worlds: New Histories of the United States and the World” held in October 2021, Katie Fapp (Oxford) and Alex Penler (LSE) reflect on the United States’ place in the world from the perspective of women’s and gender history. Sharing insights from their doctoral work, they explore how the intersecting histories of empire, nation-building, women’s rights, and public diplomacy shaped the contours of U.S. power and influence in a globalising world between the Civil and Cold Wars – not only placing the United States in the world but bringing women to the centre of its transnational histories. Katie Fapp’s remarks are reproduced below:

In the autumn of 1912, suffragist Carrie Chapman Catt was aboard a steamer cutting across the Pacific towards San Francisco. She was taking this opportunity to rest after a long time from home. The suffragist had steamed, railroaded, drove, and sailed around the world over the past year and a half; setting out from Southampton, Catt then ventured onto South Africa, Egypt, the Ottoman Levant, Ceylon, India, Burma, Dutch East Indies, Philippines, China, Korea, and Japan. While Catt had taken tours abroad before in the name of women’s suffrage, this had been her first foray outside of the West, and indeed to the American territories in the Pacific. Her expedition through the Pacific World revealed much about the nature of the international women’s rights movement in this period. Just one example of such is how it provides us with a new way to consider American women’s role in foreign relations history in this region prior to World War One.

As with many other fields, the historiography of women’s rights was not unaffected by the transnational turn. This was a particularly novel consideration for women’s suffrage, a topic previously thought to be only national in scope. The varied activity of suffragists in international and transnational spaces suggested otherwise. Historians have been hard at work researching the many forms that this activity took, however most of this work has focused on the transatlantic. My own work moves our focus away from the Atlantic and towards the Pacific, between the years 1893, when New Zealand became the first self-governing country to enact universal woman suffrage, to 1928, when the first meeting of the Pan-Pacific Women’s Association marked a new page for women’s internationalism in the region. Whilst connections across the Atlantic were undoubtedly easier to make, American woman suffragists nevertheless also sought to support their cause across the West and into the East. They engaged with the Pacific in numerous ways, from admiring their progressive Australasian sisters or petitioning Congress for the inclusion of women’s suffrage in organic acts, to globetrotting in the name of women’s suffrage or reading updates from said globetrotters if unable to travel themselves.

Mrs Carrie Chapman Catt with the flags of 22 nations, 1917 (Library of Congress)

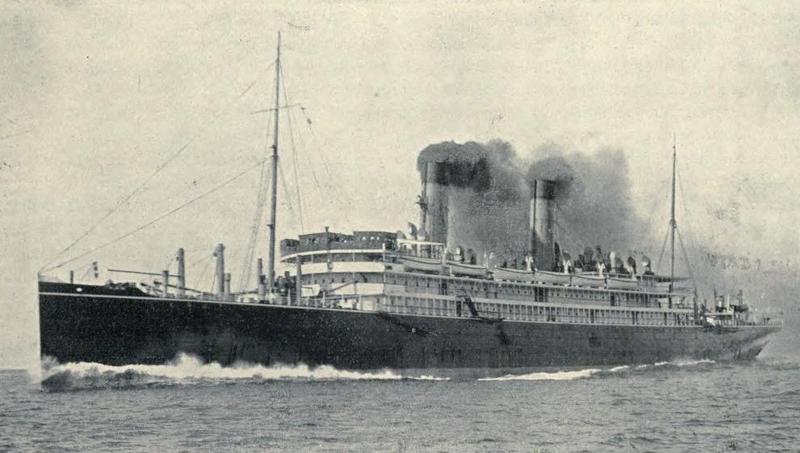

Chiyo Maru Steamer, from 'Japan to-day: A Souvenir of the Anglo-Japanese Exhibition held in London 1910' by Mochizuki Kotaro, Tokyo, The Liberal News Agency (Wikimedia Commons)

One such traveling woman was Catt, who ventured halfway across the world in 1911-1912 in the name of women’s suffrage. Alongside Dutch suffragist Aletta Jacobs, the International Woman Suffrage Alliance President forged ahead into the non-Western World to search for suffragists, observe the lives of women, and further unite them into a global sisterhood. In undertaking this “suffrage expedition”, the two became more than simply tourists – they were expeditionists, documenting and observing the status of women in parts of the world unknown to them in order to share this knowledge with suffragists back home. As such, their travels took on ethnographical and imperial tones that earlier tours across Europe lacked. While the entire expedition challenged and surprised the two suffragists, time spent in the Pacific especially revealed the pitfalls international-minded suffragists could encounter while trying to organise the women of the world. Taken as a whole, the expedition and others like it provide one window into how women engaged in more informal approaches to US foreign relations in the Pacific prior to World War One.

Catt’s experiences between the Philippines and China highlight just some of the challenges she encountered on the expedition. The American imperial endeavour underway in the Philippines stoked her own sense of American exceptionalism. This was particularly true in regards to the role women had in the massive infrastructure projects working to transform the archipelago into a beacon of progressive modernity in the region. It did not matter so much that women did not have the vote (after failing to be included in the Congress-made Philippine Organic Act of 1902) – Catt believed that with American know-how and women at the helm, the Philippines were sure to be a lead player in the progression of humanity. Her experiences in China, however, significantly challenged her belief that American women were leading the way in these progressive endeavours in the region. This is because she and Jacobs arrived in China at the perfect time to witness women sitting in the Guangdong provincial assembly (before they were removed by a national statute mere days later). Witnessing women participating in government, even if it was just one provincial assembly, was a stark reminder of the barriers that she herself faced as an American woman, still without the vote twenty years into her suffrage career. Contrary to the pride she felt in the Philippines, her time in China was a reminder that Americans were not, in fact, preeminent in the matter of women’s rights globally.

These circumstances are just two small examples of how Catt’s expedition can open new avenues to consider both woman suffrage and their involvement in American foreign relations in the Pacific. This expedition, and others like it, such as Maud Wood Park’s expedition in 1909, provide an interesting opportunity to consider more informal approaches to women’s role in U.S. foreign relations. Catt headed into new territory ¬– literally and metaphorically – during the Pacific leg of her expedition. What she found revealed the many complications involved in attempting to forge a global sisterhood in a world of empire. But the inroads she made there, in the name of woman suffrage, preceded and influenced the more formal international efforts made in the region in the interwar era. As such, the expedition attests to the importance of analysing the role informal women’s networks played in the wider scope of foreign relations history.

Katie Fapp is a second year D.Phil. student at the University of Oxford. Her work focuses on the American woman suffrage movement in the Pacific World. You can follow her on twitter @K8efapp.