Women’s Worlds: New Histories of the United States and the World (Part 2)

As part of the American History Research Seminar’s “Women’s Worlds: New Histories of the United States and the World” held in October 2021, Katie Fapp (Oxford) and Alex Penler (LSE) reflect on the United States’ place in the world from the perspective of women’s and gender history. Sharing insights from their doctoral work, they explore how the intersecting histories of empire, nation-building, women’s rights, and public diplomacy shaped the contours of U.S. power and influence in a globalising world between the Civil and Cold Wars – not only placing the United States in the world but bringing women to the centre of its transnational histories. Alex Penler’s remarks are reproduced below:

“Two for the Price of One”: American Diplomatic Wives in the Early Cold War

In his 1956 guide, The Diplomat’s Wife, career officer Richard Boyce wrote that ‘in no other walk of life is a wife so vital or her activities and conduct so important to her husband's career’.(i) He explained that in no other profession could wives either ‘spell success or failure’ for her husband. Ambassador Harlan Cleveland took it a step farther by declaring that diplomatic wives often ‘make or break their husbands’ career—and U.S. foreign policy as well’. A 1964 exhibit at the U.S. Department of State on the activities of Foreign Service wives abroad later called them a ‘strategic diplomatic resource’, a phrase coined by then Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs, Katie Louchheim and repeated frequently by Secretary of State Dean Rusk.(ii)

A long-time slogan in the U.S. Foreign Service was “two for the price of one,” and this remained an important theme in many diplomatic wives’ oral histories and memoirs. When labour expert Esther Peterson arrived in Sweden as the wife of the Labor Attache in 1950, she was loudly greeted by the ambassador that he had just gained ‘two for the price of one!’, much to her chagrin.(iii) This was not just a catchphrase; it was an explicit policy by the State Department and appeared in official documents. Diplomatic wives were employees of the U.S. government with a rank derived from her husband, and directly reported to the wives of her husbands’ superiors. While wives had not signed a formal contract, with their husbands' signature, the U.S. Department of State considered them employees.

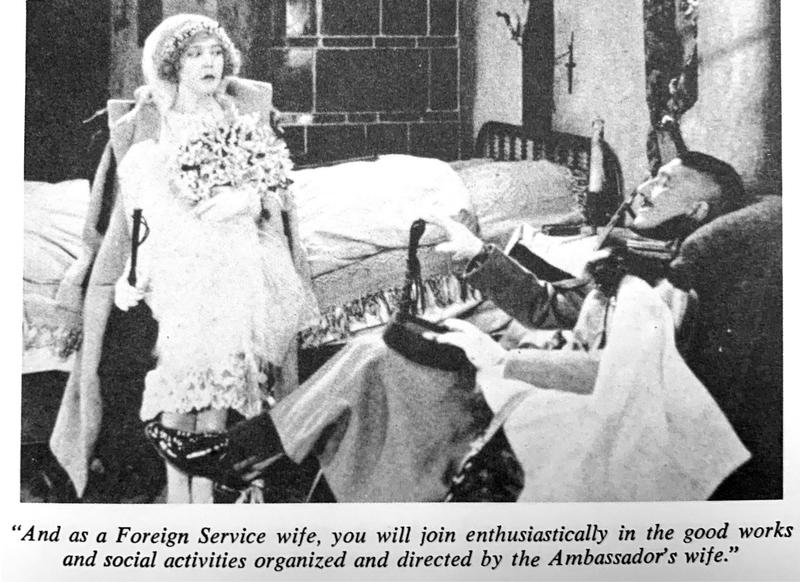

The booklet “Life and Love in the Foreign Service” used old silent film pictures with captions written by Bob Rindan, Si Nadler, and Bob Sivad in the 1960s to spoof diplomatic life. They ran in the Foreign Service Journal between 1959 and 1969.

The first board of the American Association of Foreign Service Women, 1960

Within the primarily male upper echelons of the U.S. government, “two for the price of one”, was accepted without question through the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s. Vice President Hubert Humphrey, arriving in New Delhi in 1964, proudly proclaimed that Ambassador Bowles was lucky to have ‘two for the price of one’ in the number of wives serving at that mission.(iv) Other officers were handpicked for assignments because it was well-known their wives were active members of the mission.(v) An older generation of wives were just as proud of this. Scholars should assess why this was such a beacon of pride for the men and women of the U.S. government. By examining the politics of the era, it is straightforward to understand. Examining the infamous “Kitchen Debate” between Richard Nixon and Nikita Khrushchev, one begins to recognise the perspectives of male decision-makers. Nixon did not understand that Soviet women found fulfilment outside the home and instead boasted about the fact that attractive “happy” homemakers meant American superiority. State Department and the Foreign Service were notably proud of their “two for the price of one” policy not only because it saved them necessary funds, but also because it represented concurrent American values, as least those most in line with U.S. policy.

Sociologist Hanna Papanek’s two-person, one-career theory developed in 1973 allows scholars to examine the role of diplomatic wives within the conceptual framework of gendered labour patterns.(vi) For Papanek, even though diplomatic wives’ labour exists in the public sphere, as well as the much more hidden private sphere, these women’s work was still devalued. This directly relates to the wives who felt that even though they were significant enough to be included in “two for the price of one,” they were seen more as an afterthought, something to smirk about upon arrival. Because their diplomatic work more directly related to soft power and not harder subjects like security or economics, their work remained undervalued, though not wholly devalued as Papanek suggests. As diplomacy changed in the Cold War, wives’ value increased.

The role of the Foreign Service wife grew in importance after the end of World War Two when the United States became a major power and the Foreign Service rapidly expanded. By the early 1950s, the State Department had incorporated diplomatic wives into their instruction and promotional materials, and these wives reached their peak involvement in the 1960s, before the women’s liberation movement helped compel the government to classify them as private citizens in 1972. During this period, Foreign Service Wives, as they collectively referred to themselves, had the option to take a “Wives Course” at the Foreign Service Institute in Arlington, Virginia, which covered subjects from American Art to answering U.S. critics abroad to combatting communism.(vii) Many embassies installed briefings for wives on geopolitics and local culture, invited wives to country team meetings, and some senior wives even had security clearances so they could further be of help to the U.S. mission.

With the changing of diplomacy, the wives’ role transformed, but so did the amount of influence they could have. No longer was their sphere of influence solely within the domestic, based only as whispers in her husband's ears or an argument won at a dinner table. Now a wife could make her country's foreign policy clear by choosing which charity to volunteer with, what clubs she attended, and what she said to the press. It was now more critical than ever before to win goodwill and soft power through people's hearts and minds, and women were expertly placed for this task. It was no longer a monarch a diplomat had to convince, but in young democracies, an entire population and women made up half of these. This gave all women more power than ever before as they stepped further into the public domain.

Among the Foreign Service career officers and State Department itself, it was commonly known that an effective wife helped her husband's career. As career wife Lucy Briggs explained, an outstanding officer was never affected by his wife's action, even if she was terrible, but a mediocre officer could benefit significantly by a skilled, supportive, and sociable wife. While individual officials might privately and even publicly acknowledge the vital role wives played in diplomacy, the majority of wives felt, and still feel to this day, that their work was unappreciated and unrecognised. This sits within a broader context of American women and wives both in the United States and abroad, who faced lack of acknowledgement for invisible labour in the home. This invisibility, combined with the general challenge of measuring people-to-people diplomacy, makes it hard to assess their impact and influence, but by examining their changing role, the framework of the “two for the price of one” system, and individual case studies, it is possible to see the strong effect they had.

(i) Richard Fyfe Boyce, The Diplomat’s Wife (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1956), 2.

(ii) Typescript of “Showcase of American Women Around the World” An Exhibit by the Association of American Foreign Service Women, Bureau of Administration: Records Relation to the Publication of “An Overseas Wife’s Notebook”, 1962-1965 (OWN), Box 3, Records of the Department of State, Record Group 59; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

(iii) Esther Peterson, oral history interview, Frontline Diplomacy: The Foreign Affairs Oral History Collection of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training series (hereafter ADST), Manuscript Collections, Library of Congress, Washington DC, interview transcript, page 4.

(iv) “Showcase of American Women Around the World”, OWN, Box 3.

(v) Hazel Sokolove, ADST, 13.

(vi) Hanna Papanek, “Men, Women, and Work: Reflections on the Two-Person Career.” American Journal of Sociology 78, no. 4 (1973): 852–72.

(vii) Mary Vance Trent, ADST, 3.

Alex Penler is a PhD candidate in the Department of International History at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Her research looks at the intersection of marriage, gender, and international relations with a focus on the relationship between gender and public diplomacy in the Cold War. You can follow her on Twitter @apenle01.